Solo exhibition – Sopron Museum

The National Medal Biennale was founded forty years ago this year. In the previous exhibition, the independent chamber exhibition of the younger sculptor and medalist László Szlávics, who was awarded the Béni Ferenczy Grand Prix, can be seen in the small hall of the Lábasház in Sopron.

Of the works made in the eight years since the previous Grand Prix, 78 carefully selected works are on display.

In the catalog of the National Medal Biennale, art historian László Beke wrote an introduction to the artist’s works available in English and German.

The exhibition can be viewed from June 18 to August 6, 2017. Lábasház, Sopron Museum, Sopron, Orsolya tér 5.

The solo exhibition was directed by: Viktória L. Kovásznai

Exhibition of László SZLÁVICS jr., winner of the Grand Prize of the 20th National Biennial of Medal Art

Medal artist László Szlávics jr.: a lesson in contemporary (art) history for viewers

The exhibition plan of the Sopron Medal Biennial Grand Prize winner László Szlávics Jr. is one of the most logical and cogent exhibition plans I have ever seen. It consists of six showcases, each evolving from the previous one or from the rest. But this logic is deceptive, for each showcase (group of art works) is interrelated with the rest by a variety of threads. It is not really logic (art rarely obeys the rules of Aristotelian logic), but rather a conception, or an idea that may undergo several modifications until the opening of the exhibition.

The writer of the catalogue introduction braces himself to face up to the selection of art objects, trying to analyze it so as – allegedly – to help the viewers understand the works. The artist, on the other side, sees his works differently. Actually, there is a hardly concealed struggle between critic and artist here, which is only alleviated by the fact that criticism is different from an introduction, the former may as well be negative, but the latter may not go further than being indifferent. A sort of “healthy compromise” emerges between the two which might also be called a reading.

Let’s see then what can be read out of the works in each of the six showcases.

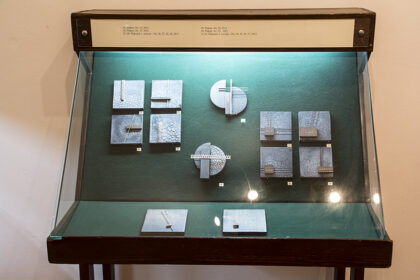

1. Showcase: For István Harasztÿ’s Birthday I-X (2009-2016). The series pays tribute to the creator of the most recent wave of kinetic art in Hungary, István (“Édeske” [Sweetie]) Harasztÿ. It was he who kept stretching the boundary of the medal with his moving metal disks already in the last century. With sympathetic humour Szlávics improves on the celebrated master’s inventions, even adjusting the titles to him: Marking Time, In the Vanguard, Latitude, Gateway, Elusory, Meander, etc. – that is, diverse allusions to the – mostly magnetic – movement of metal balls and other small metal objects on the surface of discs. A whiff of humour may be suspected when the actual anniversaries behind the objects created in the seven years are inquired about, knowing that the master was born in 1934… the 75th was then the first.

Here belongs the cycle in honour of Szlávics’ other master Agamemnon (Memos) Makris (2009) – and the commemoration of the Greek town Patras with house facades built from pieces of burnt wood with staples (!). Is a wooden relief still a medal when only the 15cm x 15cm overall shape preserves the memory of one-time bronze or precious metal reliefs? Speaking of peculiar place names, we may mention Torii and Röjtök – the latter still familiar to the Hungarian ear (as the first member of the village name Röjtökmuzsaj and also as an alternative to rejtek ‘hide-out’), while Torii may be the ancient name of Torino, or a Japanese noun… as it turns out, it is the name of the famous Japanese gates (2008).

2. Showcase: Plaques (2012). The reference to the medal prevails but regarding the use of materials, we should rather speak of collages or assemblages here. In addition to burnt wood, iron and brass elements also appear. Wood is reminiscent of cracked soil as well. No.31 and No.32 generate associations to Lajos Kassák and László Moholy-Nagy. Ontogeny follows phylogeny? While medal art, like the related genres of coins, or also postage stamps and seals, began to define itself conceptually, it arrived at the ready made and objet trouvé, and proceeded even further to autonomous object creation and surface execution.

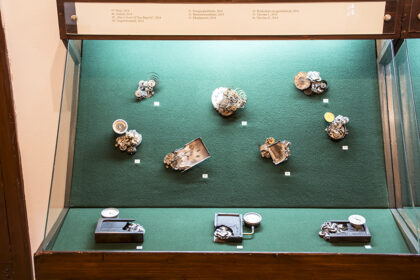

3. Showcase: About time. Clockworks (2014). Apart from involving newer and newer genres into the production of his “medals”, Szlávics is also busy creating metaphors. The exposure of cogwheels, springs and other parts is conceptually complemented by peculiar titles, temporal references such as Ancient times, Past Time, Moment, Music Machine, Soviet time (“Slava” clock from the former Soviet Union), Hommage à Jules Verne.

4. Showcase: About time. Shattered clockworks (2014). Barring the size of the exhibited objects, this showcase has nothing to do with the medal whatsoever, but conceptually it is connected to the previous vitrine. Some of the pieces suggest a cataclysm. The famous slogan of John Lennon and Yoko Ono – “War Is Over! (If You Want It)” – announced the end of the Vietnam war. In a Firestorm (a technical term of a nuclear disaster) everything gets deformed, even melted away. You can’t help recalling Dali’s Melting Time metaphor. The other (shattered) type incorporates metaphoric linguistic plays in the titles: Space Warp Meter, Wormhole Gauge, Dimension Modulator, Declination Marker, Portable Latitude Searcher. Harasztÿ could exclaim again: “I might have made them myself!”

5. Showcase: Shattered cameras. Hommage à Robert Capa and Memento (2015). Shattering continues with the 36 mm Leica-size cameras, which appear to emerge from under the ground after a war, as it were. Reference to the famous photographer (killed in the Indochina war by a mine) commemorates photo reporters of all times.

6. Showcase: Human eye and camera lens. “Big Brother” (2015) and Roswell ’47 (2016). A type of camera parts – lenses – that stare at you apprehensively when you catch their glance emerged from the sand like archeological finds in the previous showcase, too, in the Memento series. “Big Brother” is now familiar to everybody from George Orwell’s novel 1984: Big Brother is watching us day and night, there is no hiding from him. On the other side, the Big Brother was the Soviet Union where several of the cameras were produced. So far, that would just be cheap political humour, if you failed to realize that the component part termed “optic” i.e. lens is only the mount of the lens and the place of the actual lens is taken by an artificial glass eye. This recognition endows all implications with polysemantic meaning. One piece of the cycle, “Minority Report”, is quite intricate because, for one thing, the lens-eye is covered by the lamellae of a central lock. Thus, the cycle is not only about looking and seeing, but also about the media and communication.

The background to Roswell ’47 is most probably only known to those who look it up in special literature. The small town in New Mexico was the venue of the first major UFO disaster in the last century, in 1947, where extraterrestrial wrecks and remains even of living beings were allegedly found. Research gained momentum at the end of the last century, Szlávics joining this revival of interest. His most important find is a glittering steel plate emerging from the sand with strange signs (of writing?) on it, which may inspire associations to the golden plates of the Prophet Mormon or to the information about the Earth placed in the Venus rocket (1961). In both cases we have strange extraterrestrial communication.

The internal associative network of the six showcases illustrates how László Szávics Jr., perhaps the most spectacular innovator of the Hungarian medal, has covered the historical path of redefining the art of the medal over the past decade, from the traditional genres and techniques of sculpture and relief, touching on metal working, goldsmith’s art and jewellery, in no little measure upon the influence of conceptual art and object art. He has pondered on the interconnections of art and science, technology and culture, and arrived at comprehending the current state of the media and communication.

László Beke